The other writer of this newsletter once told me an anecdote about a series of travels a member of his family took with their friends. This group of people, who originated from the New World, travelled around Europe, visiting various historical sites. When they returned home, their friends’ families asked how their trip had been. ‘Eh, it was alright. It was just a bunch of ruins.’

Clearly meant to be a sign of ignorance, or adolescent boredom, it does reveal that the ruin – that respected motif in Western culture – does not strike the same spart in everyone. Apollon Maykov is in many ways a poet of ruins. Functioning on memory, he blends the idyllic with the historical and mythological to forge a ‘no-longer’ vision of Russia. Simultaneously, he directly acted on one of the primary sites of ruin—in his second book Sketches of Rome. This volume does about what one would expect, hiking up the romanitas in the city, turning it into the Mediterranean ideal.

Yet, in 1848 (six years after Sketches of Rome) Promenade in Rome with my Acquaintances was written, giving move valuable insight into ancient Rome. One of these ‘acquaintances’ with which he walks with was a Russian official who commented:

Is this all? These broken stones (oblomki)? Well, to tell the truth, apart from

the Coliseum, there is nothing good to look at. Why don't they spruce

things up here? I pictured the ancient city in an entirely different way. To

begin with, I would not allow these bulls here and would not have tolerated

this rubbish. Nothing should grow over here. Secondly, I thought that there

is a real ancient city, that this is a separate city, with palaces one can visit,

and with real streets.

— Apollo Maykov, Promenade in Rome with my Acquaintances

Maykov was particular, by the fact that he was a Russian who did have a great appreciation for ruins. It seems as though the spectacle is completely meaningless for a great number of people. Yet, the universality of ruins as having a cultural value is far overstated. It was only in that ‘disenchantment of the world’ that the ruin as a site of rumination and thought became valuable. Prior to the Enlightenment, a ruin was perhaps of value to collectors or architects, yet even then, little was done in their preservation. The extent of spolia during Medieval times integrates the past, rather than separating it. Furthermore, any artefact or ruin had little value were it not from Classical Antiquity, or from Exotic origins.

Global trade meant that assertion of cultural importance was far harder to do geographically, as one had to recognise one’s spatial insignificance. Therefore, the use of historical discontinuity became the primary method of self-preservation. By the 18th century, the ruin became ambivalent, as it functioned alongside the ideology of progress of the Enlightenment, which turned the ruin into a signifier of evolution. Decay was no longer a sign of tragedy: instead, it was like the reptile that sheds its skin, a sign of growth and age.

Given its demystification of nature and its forces, the ruin functioned on a spiritual basis, what it couldn’t say about nature, it might reveal about man. While in Voltaire’s poem about the Lisbon earthquake, some providentialist narratives remained, contemporaries made the ruin fit into a highly solipsistic framework. Quite unsurprisingly, Diderot adopted an individualistic sentimentalism regarding the ruin — bolstered by Burke’s thesis on the sublime. Given a certain level of distance, decay brings about fascination and pleasure. It functioned on the pure subjectivity of the viewer. A predictable response from his school of thought, one can think about its current cultural and political equivalents.

By contrast, the Hegelian statement on ruins starkly dismisses any gloomy sentimentalism. The interaction between ruins and the spirit ought to strengthen it. Rather than a fatalistic wreck of history, it should prompt ‘a revolt of the Good Spirit’. What use is it to us to stare at demise? The sublime as a motif is arguably a highly conservative practice. Individualising historical processes and marvels, it reduces it to a sensory experience, acting as a direct catalyst for inertia.

Arguably, the ruin functions as two sets of movement, one of which is the process of decay, and the other is the rebuilding. They each function after different historical models: the first one making the process into one of gradual disintegration. The other moving in two lines, the cyclical line which rolls along a linear ascent.

Broadly reawakening the phenomenological study of the ruin, Georg Simmel articulated the uniqueness of the architectural project. It existed in the conflict between spirit and nature. The decay of construction was the manifestation of a dismissal of the Enlightenment, as nature did triumph over man. It was a mode of revenge, which also prompted a strengthening of the spirit (in the Hegelian sense). It proved the existence of the body after it had been subjected to ‘rape’. Especially when considering Vitruvianism – although it may be sluggish – it engages with age and disfiguration in an innovative sense. The 18th century was characterised by fear of age and decay erasing the ‘wind’ from the process of becoming-ruin. Its direct involvement with colonial processes may further reveal an engagement with the fears of acculturation. By performing acts of assimilation, knowledge of the fragility of man required the comfort of some symbol of preservation — which became the ruin.

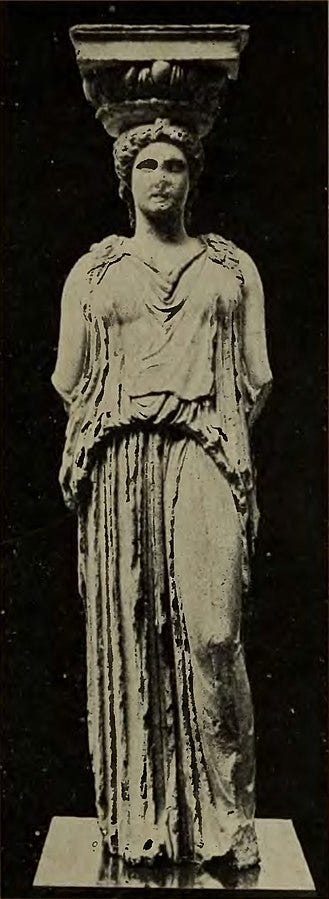

In another manner, the ruin as body engages with the discourse on nationalistic mythmaking and architectural gendering. The classical orders put the Doric column at the base, signalling its strength, while the feminine Corinthian sits atop, representing fragility and softness. Scorched-earth and other practices of war oftentimes model treatments of architectural projects with the treatments of foreign women. The most classical example of this is, of course, the caryatid. The women of Caryae were immortalised as columns of shame for their betrayal and prostitution in the Greco-Persian wars.

The modern ruin, however, barely exists due to nature. The primary sites of architectural destruction and decay have incredibly little to do with it. Pre-modern works are indeed in a continuous state of decay — yet preservation efforts and archaeological knowledge invest in the spirit, bolstering their preservation. The current ruin is only made by the spirit, making it far less glamorous. In addition, the 20th and 21st centuries saw the ruin in a non-completed manner. One clear example may be the Tatlin Tower, which brings in the unique Russian view of ruins.

One may also think of a typical fixture in Lebanon’s mountains: abandoned, unfinished houses. They were usually built by families who planned to have a home in the hills, their construction stops due to various reasons (usually economic). As skeletal structures, they reveal the deeply unromantic ruin. The ruin is usually conceived as a materialised parallel of the processes of historical collapse. Having never been built, the entropy of history went elsewhere.

The problem with ruins is that their meaning cannot be controlled. They threaten to imprison us in the unguarded labyrinths of the past, and they also promise to open imaginary escapes. In his prison sketches, Piranesi staged scenarios of exquisite claustrophobia and devised escapes from captivity relying on the power of his designing imagination. Like Houdini, we hope to become escape artists who leave the towers behind at just the right moment. Ruins are not only anthropomorphic but also anamorphic: in our imagination they morph into different shapes like clouds or stones; they make up the invisible cities of our dreams and nightmares, conjuring them to life; and they reveal the memento mori in every lively tableau, like the skull in Holbein’s famous picture. We frame the ruins, and they frame us.

— Svetlana Boym, ‘Ruins of the Avant-Garde, From Tatlin’s Tower To Paper Architecture’