By Lucia Billing

The third studio album from the U.K. based band black midi was released on July 15th, 2022. Hellfire is a jazz-rock experimental album about Hell and the hellish forces in society. In its 38-minute runtime the full-length LP, “tell[s] the tales of morally suspect characters.” The members of black midi are remarkably well-read, with their musical inspirations being more high-brow than expected. Hellfire takes inspiration from Kurt Weill’s cabaret music, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Zappa, and Richard Yates. Despite the work's numerous influences, I think it leaves the listener with a distinctly Modernist taste. I find similarities between Hellfire and a century old art movement, Weimar’s New Objectivity, particularly interesting. Thus I explored these parallels in order to gain an understanding of how black midi created such an authentically modernist work one hundred years too late.

The setting of Hellfire remains ambiguous; in the song Sugar/Tzu, Greep recalls a boxing match that took place on “February 31st, 2163”, and in The Race is About to Begin, he rambles on about invented cities: “Salafessien”, “ Schlagenheim” “Sunterum” and “Sunterime”. The sense of disorientation that the complex music provides is accompanied by its indecision and ambiguity in place and time. As you listen, you are unable to put your foot down and settle into your surroundings, for the lyrics constantly remind you that you are not in a real place. One cannot pinpoint Hellfire geographically, however, the light in which it portrays its themes is decidedly reminiscent of interwar Weimar Germany. In particular, it has a plethora of similarities to New Objectivity, contemporary to that time. The art movement was characterised by scrutinising and often cynical visions of Weimar, in particular the city of Berlin, as it rapidly evolved into a hotspot for indulgent and decadent nightlife while still carrying the remains of World War One.

The trauma of war is a theme which consistently pervades both oeuvres. In Welcome To Hell, the album’s fourth song, it takes centre stage. The song recalls the shore leave (break of seafarers spent on dry land) of Tristan Bongo, a soldier who finds himself pressured to sleep with a prostitute. His commander, who is the one narrating, aggressively berates him for his fragility, which probably resulted from time in the trenches, “So don't tell me of your troubles, your emotional grief” he says. The song explores the expectations of hypermasculinity and nonchalance in the face of sex and war, which our subject is unable to perform. Honour is presented only to those who exert callous indifference and cruelty in wartime, since “To die for your country does not win a war; To kill for your country is what wins a war”.

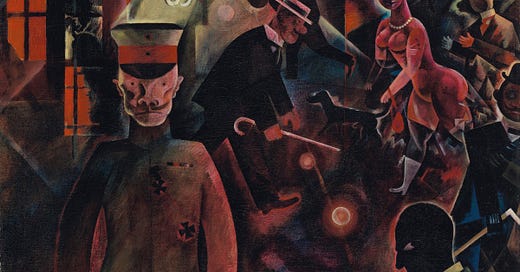

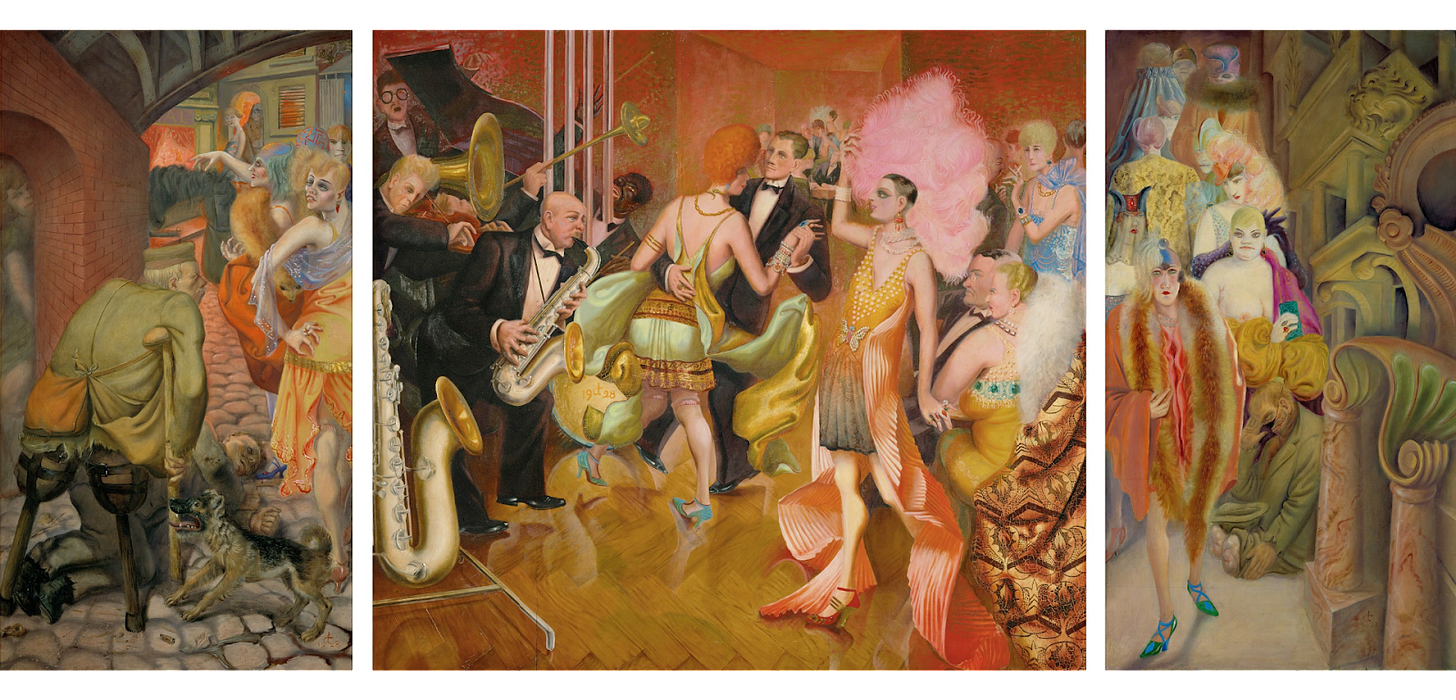

New Objectivity is - similarly to Hellfire - haunted by war. Both Otto Dix and Max Beckmann, two major artists of the movement, owe much of the motifs in their work to their traumatic experiences in World War One. Some of Dix’s most renowned work, including The War and Stormtroopers Advancing Under Gas coldly depicts the cruelty and horror of the Great War. If art about the war is characterised by horror, art about the interwar period is characterised by cacophony. In the new glitzy salons and streets of Berlin, indulgence is encouraged, sex and crime grasp the young while the demented gueules cassées wander in the peripheries. In the outer panels of Otto Dix’s work Großstadt (Metropolis), colourful scantily dressed prostitutes slink by injured veterans, who have been left to the dogs. In George Grosz’s Dangerous Street, the underbelly of Berlin is showcased once again. The foreground of the painting is occupied by a soldier, who stands face-forward towards the viewer with absent eyes. To the left, a prostitute, seemingly naked, is walking. Her face resembles that of a gueulle cassée, as her bulging eyes and bright teeth produce a skull-like resemblance. Both of these works provide insight into the jumbled superposition of the new Weimar and the old.

Prostitution is used as a symbol of the decadent societies in which the works take place. In interwar Germany, many widows were forced to turn to prostitution in order to survive, as their husbands were killed in the war. Similarly, in Welcome to Hell, there is talk of “temptress widows”. The Berlin of this era has since been portrayed as a breeding ground for sexual freedoms, where the Sex Reform movement gained momentum. Left-wing parties were especially supportive of decriminalisation of prostitution, access to birth control, as well as acceptance of homosexuality and transsexuality. The relative acceptance of prostitution within this culture causes it to move into the light in its artistic products. For instance, George Grosz’s watercolour painting Circe, which depicts a prostitute kissing a porcine man. The motif of deplorable, boorish men in sexual relationships with debauched prostitutes permeates New Objectivity.

In Hellfire, the song The Defence becomes the primary communicator of this theme. The song is told through the narration of – presumably – the devil, who is recounting the routine of one of his disciples, a brothel owner searching for men. He makes it clear that those frequenting the brothel are not honourable, instead being “The virile, pathetic, and lame”, and that they weep of guilt “Every night.” Later on in the song, the narrator attempts to justify prostitution and owning a brothel, he states “A brothel is a business no different than a bank; As safe and as formal and sanitary.” Although this line seems to present brothels as clean and organised, it is rather a comment on banks and their fraudulence. The line about banks calls to mind the Weimar hyperinflation crisis, as the nation was plagued by economic decline and lack of trust in financial institutions. The song also reminds the audience of the crime-ridden, unsafe world in which the song takes place. It does this through another justification of prostitution as being a sanctuary for women “Without my aid they’d be in chains; Or disembowelled in a backstreet lane.” The economic decay and high rates of crime are used to justify the sexual exploitation of women. The world of Hellfire is keenly aware of its debauchery and filth, and attempts to find some beauty within it, Greep states in an interview with The Line of Best Fit : “I’ve always liked the idea of doing something that’s quite perverse on the surface, quite horrible, but then trying to write that in a more poetic, or, on the surface, beautiful way.”

Hellfire and New Objectivity are also parallel in their composition. Although it is not true for all works within the movement, much of New objectivity paintings are composed of numerous characters, placed as if in a fresco. The characters are grotesquely disfigured, expressive and caught up in their actions. This can be found in works such as The Night by Max Beckmann, Suicide by George Grosz, and Skat Players by Otto Dix. Rather than an exploration of any particular character, the paintings produce a snapshot of the chaotic landscape in which they inhabit. The characters in the works are barely human, they have become symbols and caricatures of the most deplorable aspects of society. This method of composition is most closely found in The Race is About to Begin. The setting of a racetrack serves as a background for the exposé of impotent, idiotic characters which clutter Hellfire. Geordie Greep urgently enumerates “Lucky Star, Eye Sore, Doctor Murphy, Sun Tzu, The Clap, Mr. Winner, Spot, Wallace, Mrs. Gonorrhoea, Perfect P, Deadman Walking, and The Company Favourite”, producing rambling portraits of those attending the race. We learn of the perversity of this cast, as the “reporter was caught getting sweaty in the stable”, referring to an engagement in bestiality. There is little to no sight of any morality or thought, since, as Greep states in the opening line of the song “Idiots are infinite, thinking men numbered.”

The key to the album – and to New Objectivity – lies in, I believe, the outro of the song. After the fast-paced, discordant rambling of Tristan Bongo, soft guitar-plucking and atmospheric horns are all that remain.

The clown can be a martyr

The whore can be an angel

The hack becomes a master

The crass becomes divine

The infinite, infinitesimal

All sins irrepressible

No use digging holes to hide

The rupture comes and leaves no stone unturned

So don’t wish for anything

Hellfire and interwar Weimar are worlds in which previous social codes are suspended. New Objectivity does not aim to depict the sanitised, moral, saintly view of the world. Rather, its subjects are that of the clown, the whore and the hack. It is them who are put in the triptychs (which up until the 19th century were almost purely religious). Hellfire and New Objectivity produce images of societies in which the decadent underbelly has become the norm. There is no concealing of the sins of society, for war and economic disparity have left them visible to all. The societies presented are essentially purgatories, neither of the projects present their characters as fundamentally evil, yet, they are constantly tricked, fooled, and seduced by devilish forces. While the characters of Hellfire are destined to Hell owing to their stupidity, the people of the Weimar Republic were fated to economic depression and the rise of Naziism.