By João Ruy Faustino

Reviewed:

Knulp: Three Stories from Knulp’s Life (Herman Hesse, 1915)

Demian: The Story of a Boyhood (Herman Hesse, 1919)

Siddhartha: An Indian Novel (Herman Hesse, 1922)

Steppenwolf (Herman Hesse, 1927)

I

There is the deeply personal, private, ethical, sentimental concern; and the communal, universal, moral, political concern. Religion somehow exists on that spectrum. Currently, it is facing the struggle of finding a balance between the private and public spheres of our lives, a strenuous task for any institution. Thus, ritualistic forms of religion are being hollowed out.

It appears that this is nothing new. The most important events of the XX Century involved the creation of new forms of religion that could accumulate or supplant the old ones. At first, these secular religions replicated in great part the ritualistic – formal – facets of their predecessors. Marxism, for example, replaced God with History, the church with communal houses, preachings with speeches, council meetings, dialectic, and many other characteristics that defined the communal and mutualist culture of the ideology. However, by the XXI century these secular religions had either faded, or their formal features had entirely disappeared.

Communal aspects of our living are dissolving before our eyes: church attendance is declining, membership to unions idem, and affiliation to political parties have crashed. This is merely a reflection of a process where nearly all sources of shared institutions are disintegrating. Identity, authority, community: all of them emptied and made impractical for us. All of it was sacrificed in the name of the Self.

A plethora of economic – compounded by ideological – causes have turned the self, and the freedom of the self, into the only universal value in our societies. What is currently fomented by society’s ideology, its current Culture, is a path of self-realisation – bildungsroman in German – for each and every individual. Every liberal precept seems to point towards that direction: the freedom of an individual is only limited by the freedom of others, that no state has the right to impose or recommend a form of life, etc. In that respect, existentialism and nihilism seem to be wholly compatible with such a state of affairs, with these being powerful philosophical currents today. For many years it was good and fun. There weren’t many upheavals, things worked out.

Morality as a posture – goes against our taste today. This too is progress: just as it was progress when religion as a posture finally went against the taste of our fathers, …

– Friedrich Nietszche, in Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future

As long as morality resisted through our forebears, and a stringiness and rectitude during the formative years was appreciated, there was a possibility that this new ‘order’ could last and deliver its promise. Indeed, the previous era, with its merely superficial appeal to morality, led to disillusionment. However, is our current age truly fomenting a clarity of purpose? or are we just lost (and oppressed) in a different way? Before we only knew we had to get out, now we don't know where to get in.

II

The idea of self-realisation is awfully important when religion is absent. There are questions that we just need answers to, and when there’s no institution to provide them we can’t help but look at the first thing we all believe: ourselves.

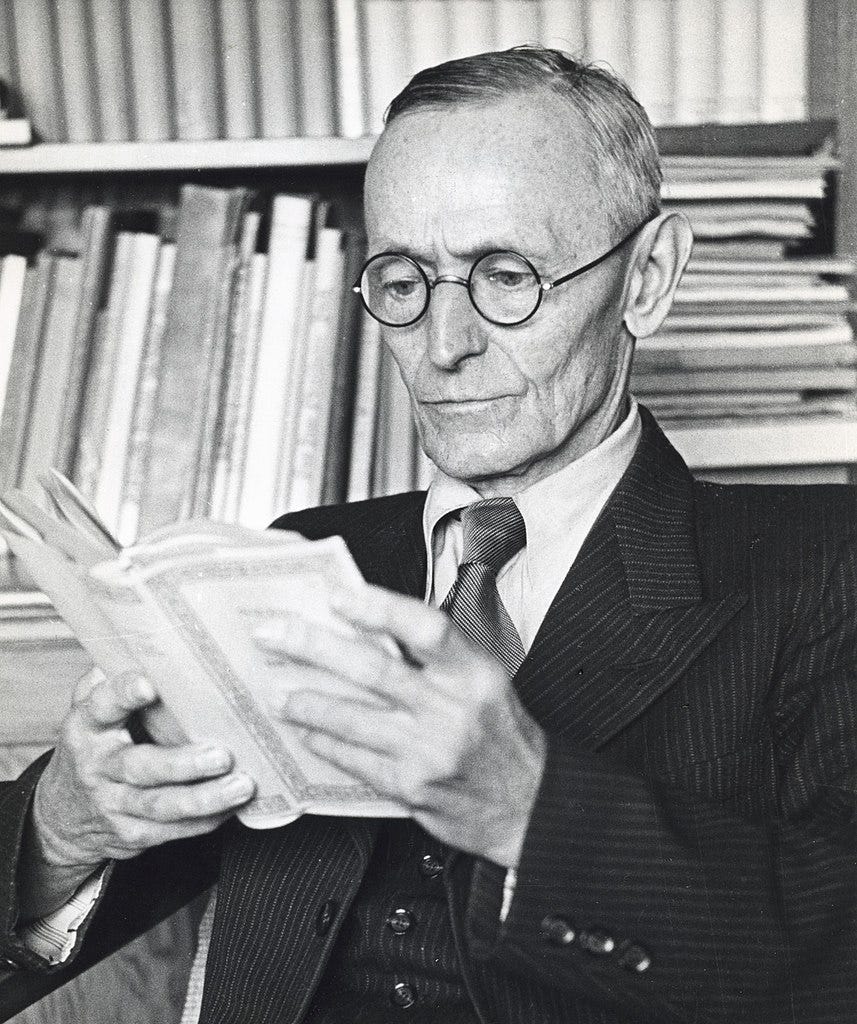

The writings of Hermann Hesse (1877-1962) have thus given spiritual and proto-moral guidance to those who seek it for many years.

The distinctly German character of his work, as it echos the “reflective thoroughness” of the nation’s culture, allied with its distinct Oriental influences – these themselves another sign of Deutschtum, as Schopenhauer was a pioneer in introducing Hinduism to Western culture – somehow made it appropriate for our times. It seems, at first glance, that Hesse’s politics – the politics of detachment – may provide a heart and soul to our society’s ideology. It is Hesse who makes the best appeal to what the absurdists call decency. In his books there are no moral afflictions, at least nothing compared with those seen in XIX and XX century literature, and so, one may come to think that Hesse’s gospel might be benign – if replicable.

And where was Atman to be found, where did He dwell, where did His eternal heart beat, if not within the Self, in the innermost, in the eternal which each person carried within him? But where was this Self, this innermost? It was not flesh and bone, it was not thought or consciousness. That was what the wise men taught. Where, then, was it? To press towards the Self, towards Atman - was there another way that was worth seeking? Nobody showed the way, nobody knew it - neither his father, nor the teachers and wise men, nor the holy songs.

– Hermann Hesse, in Siddhartha: An Indian Novel

The truth is that, despite what is written in his work, such a path to bildungsroman is highly destructive. In fact, it is dubious that any path to self-realisation without an external force guiding it has the possibility of being truly constructive to anyone but a handful of people (if that). While Hesse’s philosophy has the potential to ameliorate certain aspects of our ‘individualistic’ culture, it will certainly not fix it. In many ways, there’s no means to repair it, and it would be counterproductive to even attempt to give it any further substantive backing.

III

The figure of the wanderer is who primarily advances the undeniable allure present in Hesse’s novels.

Every known culture praises walking and emphasises its relation to thought and spirituality. Yet, Hesse takes this lesson a step further. While the characters in Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain go for walks, the rest of the moments in the novel are quite still. In Hesse’s Knulp, to name an example, there are no walks, only one: the character’s life is one boundless walk. It is a continuous peregrination that Knulp cannot escape from, despite its apparent destructiveness:

Once, early in the nineties, our friend Knulp had to go to the hospital for several weeks. It was mid-February when he was discharged and the weather was abominable. After only a few days on the road, he felt feverish again and was obliged to think about getting a roof over his head.

– Hermann Hesse, in Knulp: Three Stories from Knulp’s Life

Hermann Hesse justifies this perpetual march the following way:

Each man's life represents a road toward himself, an attempt at such a road, the intimation of a path. No man has ever been entirely and completely himself. Yet each one strives to become that – one in an awkward, the other in a more intelligent way, each as best he can.

– Hermann Hesse, in Demian: The Story of a Boyhood

The deeply introspective character of the protagonists Harry Haller (Steppenwolf), Knulp (Knulp), Demian (Demian), Siddartha (Siddartha) is the most engaging trait of his writing. The German author indeed excels at writing characters and their inner thoughts, even if all of them essentially have the same persona.

This is an idiosyncrasy that Hesse must have surely been aware about. The retrospective tone that he used to depict many of his characters is a motif. All of his characters live a discrete life that others can not help but notice and admire:

I, however, feel the need of adding a few pages to those of the Steppenwolf in which I try to record my recollections of him. What I know of him is little enough. Indeed, of his past life and origins I know nothing at all. Yet the impression left by his personality has remained, in spite of all, a deep and sympathetic one.

– Hermann Hesse, in Steppenwolf

Govinda, his friend, the Brahmin's son, loved him more than anybody else. He loved Siddhartha's eyes and clear voice. He loved the way he walked, his complete grace of movement; he loved everything that Siddhartha did and said, and above all he loved his intellect, his fine ardent thoughts, his strong will, his high vocation.

– Hermann Hesse, in Siddhartha: An Indian Novel

In a short-story entitled My Recollections of Knulp one can again discern the tone:

I listened with pleasure and without envy; only when he was standing surrounded by girls, histanned face flashing like summer lightning, when for all their laughing and joking the young things couldn't take their eyes off him, it occasionally struck me that he was an uncommonly lucky devil or that I myself was the opposite.

– Hermann Hesse, in Knulp: Three Stories from Knulp’s Life

In Demian, the author opts for a recollection of the narrator's own memories, and that is where he is most successful. That a person can be lonely, ascetic, quiet and deeply spiritual, while, at the same time revered by their equals, is more than ‘unrealistic’: it is self-indulgent. It ends up revealing more about the author than about the character being built. Even so, a person such as the one described in the first paragraphs of Steppenwolf will entice empathy in the reader, and would perhaps transmit curiosity to those who surround him:

He lived by himself very quietly, and but for the fact that our bedrooms were next door to each other—which occasioned a good many chance encounters on the stairs and in the passage—we should have remained practically unacquainted. For he was not a sociable man. Indeed, he was unsociable to a degree I had never before experienced in anybody. He was, in fact, as he called himself, a real wolf of the Steppes, a strange, wild, shy—very shy—being from another world than mine.

[…]

Altogether he gave the impression of having come out of an alien world, from another continent perhaps. He found it all very charming and a little odd. I cannot deny that he was polite, even friendly. He agreed at once and without objection to the terms for lodging and breakfast and so forth, and yet about the whole man there was a foreign and, as I chose to think, disagreeable or hostile atmosphere.

[…]

Above all, his face pleased me from the first, in spite of the foreign air it had. It was a rather original face and perhaps a sad one, but alert, thoughtful, strongly marked and highly intellectual. And then, to reconcile me further, there was his polite and friendly manner, which though it seemed to cost him some pains, was all the same quite without pretension; on the contrary, there was something almost touching, imploring in it.

– Hermann Hesse, in Steppenwolf

IV

Here is Hermann Hesse’s philosophy, to those who still don’t know, as succinctly explained in the first passage of Demian:

I wanted only to try to live in accord with the promptings which came from my true self. Why was that so very difficult?

– Hermann Hesse, in Demian: The Story of a Boyhood

Is this not our current ideology? Let’s all be honest with ourselves, our current culture no longer dictates ‘Obey your father’. Quite the opposite actually. Hesse’s modus vivendi is that of the personal exploration which is so common today: gap years, travels, drugs. And, again, I’ll ask: What has this animating principle given us?

What the world needs now appears to be an unfiltered dose of reality and a discipline that truly tackles today’s globally-scaled challenges. Despite preaching a mystical attachment to earth, Hesse’s philosophy is conclusively apathetic, hedonistic and selfish. There are aspects of our culture that need to be curbed – consumerism namely – yet what is most desperately needed is the erection of intermutual arrangements: the fostering of a belief in the collective.

V

It was pointed out earlier the distinctively Deutschtum of Hesse’s work, yet the full extent and consequences of this characteristic have not yet been fully uncovered.

Despite Hesse’s denunciation of Nazism it should be pointed out that his Hinduist ethos was fully appropriated by the Nazi regime and especially Heinrich Himmler – with the head of the SS even commenting on his diary that Hesse’s Siddartha was a “magnificent book.” The link between the regime’s ideology and Hinduism are very well explained in an highly recommendable interview with Victor and Victoria Trimondi, two specialists on the matter, given to the International Business Times years ago.

Furthermore, in Hanna Arendt’s quintessential study of the ‘Final Solution’, the author alluded to such connection:

The member of the Nazi hierarchy most gifted at solving problems of conscience was Himmler. (...) Hence the problem was how to overcome not so much their conscience as the animal pity by which all normal men are affected in the presence of physical suffering. The trick used by Himmler - who apparently was rather strongly afflicted with these instinctive reactions himself - was very simple and probably very effective; it consisted in turning these instincts around, as it were, in directing them toward the self. So that instead of saying: What horrible things I did to people!, the murderers would be able to say: What horrible things I had to watch in the pursuance of my duties, how heavily the task weighed upon my shoulders!

– Hannah Arendt, in Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil

Indeed, the philosophy of no-self is not only avoidable as a posture to take in regard to one’s personal life (ethics), it inevitably involves a tremendous moral exasperation. Removing the self from the outside world is the beginning of disaster, with anything and everything becoming justifiable – or simply outside the realm of ‘justification’.

VI

Of course, many of the preoccupations revealed here are solely political. Besides, Hesse includes many caveats to his philosophy of life – some even included here. And it’s those hesitations, those contradictions, that reveal genuine thought. Hermann Hesse truly was a literary genius. His legacy, however, has been a less positive one precisely because of his doctrine – misinterpreted or not.

In truth, Hesse’s character transpires through his novels and what is conveyed to the reader is an isolation and transcendence that might not consist of a recommendable approach:

Hesse's unpolitical image reaches its apotheosis in his own emphatic statement in the preface to the 1946 edition of Kreg und Frieden that he is thoroughly unpolitical, that the only thing political about his essays is the atmosphere in which they are written, and that he is solely concerned with that inner part of the individual which is beyond the reach of politics.

– Robert Galbreath, in Hermann Hesse and the Politics of Detachment

On one hand, this is very revealing, while on the other it is disappointing. What it takes to understand that such a committed apolitical stance is impractical is not much different from the realisation that Aristotle had millennia before Hesse:

The virtue which we have so briefly considered is moral virtue, the best state of ordinary lives as ‘political animals’. But Aristotle, as we have seen, also recognized, and indeed exalted above the practical virtues of social life, the intellectual virtue of the philosopher.

…

And so even Aristotle’s final and almost lyrical account of the true happiness for man in the last book of the treatise does not escape giving the impression of at least superficial contradiction. This true and highest happiness lies for Aristotle in theoretical science and philosophy, the unfettered exercise of the intellect for its own sake. Since it is nous which distinguishes man from the beasts, the exercise of nous must clearly be his proper activity qua man. Yet immediately after explaining all this he goes on: ‘But such a life would be superhuman. For it is not in so far as he is human that a man will live like this, but in so far as there is something of divinity in him; and just as that divinity differs from the concrete whole, even so will its activity differ from the activity of ordinary virtue. If reason is divine, then, in comparison with man, the life according to it will be divine in comparison with human life.’

At the same time he follows this up with the exhortation to disregard the advice of prudent poets (it was a commonplace of Greek literature) that it is foolish to emulate the gods. We should aim at divinity as far as lies in our power. And a little farther on he says: ‘This part may be considered to be each one of us, since it is the highest and best. It would then be absurd for a man to choose not his own life but the life of something else.’

– W. K. C. Guthrie, in The Greek Philosophers: From Thales to Aristotle

By being a ‘political animal’ one means that, besides being social animals, humans have the intrinsic preoccupation on how a community is governed – themselves as well as their peers. What is lacking in Hesse’s work, and in all of Hinduism’s world outlook, is these inescapable societal components: politics and morality.

This is not to say that the individual does not have a role, indeed it has a central role – nothing compares to it. However, the role of individuality should not go much further than the will that thankfully derives from it.

Another German genius can give us an answer, the one that fully established a metaphysics of morals: Immanuel Kant. The answer seems to be fully laid out in his categorical imperative:

Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.

– Immanuel Kant, in Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals

Notes from a news junkie

Are we witnessing the clash of civilizations?

Not flash, just Gordon.

Other teachings by Aristotle.

Interesting! We seem to have come to a similar place on Hesse, starting from different ideologies and focusing on different books of his. Here's what I just wrote: https://outlandishclaims.substack.com/p/seven-glass-beads . I don't think Hesse was exactly preaching selfishness/self-absorption. I think he had internalized the (false) idea that self-actualization and service to the world were impossible to pursue at the same time. He thought he was being selfish with his chosen lifestyle, and felt bad about it, or at least conflicted. But it is possible to find yourself in service to others (you could write one heck of a bildungsroman about Greta Thunberg, I'm sure), and it is possible to serve others by finding yourself, as Hesse did.