By Lucia Billing

Reviewed:

PORTRAITS: JOHN BERGER ON ARTISTS, John Berger (2015)

This Great Allegory: On World-Decay and World-Opening in the Work of Art, Gerard Richter (2022)

Prehistoric Painting: Lascaux or the Birth of Art, Georges Bataille (1955)

In the discussion of any art form, whether it be sculpture, music, literature, or cinema, there exists contention in assuming that the origin inherently possesses a sort of sacredness. There is a (mostly) undisputed value in the first piece of writing, the first film, or the first statue. Yet systematically, a demystification of the ‘origin’ has taken place. Some frameworks –Christian, or perhaps Rousseauian ones – inscribe a purity and sacredness to the origin which has, through secular and postmodern lenses, been contested. The Darwinian framework, and subsequent extrapolations of it have branded an air of revealing unimportance towards the origin.

We wished to awaken the feeling of man's sovereignty by showing his divine birth: this path is now forbidden, since a monkey stands at the entrance .

– Friedrich Nietzsche, Dawn, no. 49 .

While the divinity of the origin has been disputed, it is hard to deny the essential character that early relics of humanity hold. Anyone who has studied the arts has been forced to concede to Chauvet and Lascaux.

I

After the emergence of photography largely put an end to classical art, new series of contexts and frameworks surrounding the arts emerged. Just as quickly as this emergence took hold, its equivalent in scholarly and theoretical writings materialised at a greater rate. Not only could discussion of modern works take place, but a reinterpretation and reevaluation of the past as well.

Art History has become pervaded by discussions of ‘contexts’, ‘lenses’, and ‘frameworks’. These dialogues are greatly informative and revelatory. They are also quite easy to have, considering the ever-great canon of artworks behind us.

Although some philosophical approaches place more value on contexts, whether that be of the art or of the artist – the poststructuralist method has been greatly accepted into modern writings and teachings.

This approach is – arguably – based on the search for difference. It breaks up the previously unquestioned consistency of the art world. It is a search for interrelations and intersections which expand and specialise to further degrees. It finds parallels in the Derridean conception of the world as undeniably fragmented between our world and the worlds of those around us. While Derrida argues that we can never fully enter into the world of the other, the poststructuralist method of art analysis opens up the possibility for certain worlds to move into the spotlight. Thus materialising through a discussion of them. If this method of analysis relies on contexts, what can we do when we are met with an artwork that has little to no contextual information?

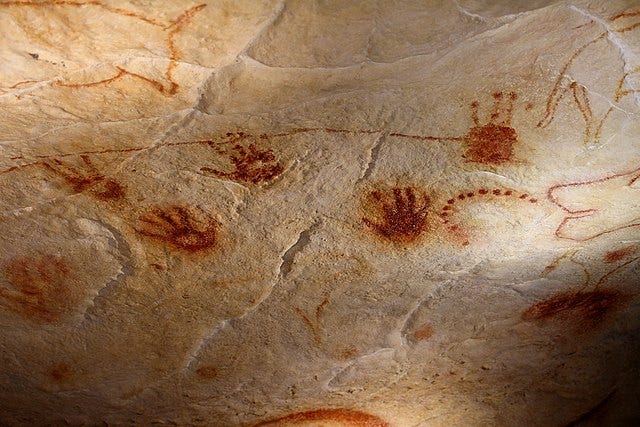

Such is the case with prehistoric art. Georges Bataille states, we “know next to nothing of the men who left behind only these elusive shadows, framed within almost nothing, unprovided with any explanatory background.” Archeological technology has helped us situate them within a loose timeframe, yet this information can often seem unimportant or frivolous. 1

Since we cannot hope to achieve revelations through these paintings’ contexts, we are instead faced with them through their universality. It is fascinating enough that caves ranging from Spain to Indonesia often possess the same motif of hands – either of palm marks or of the negative spaces surrounding them. Yet, beside choices of motifs and the commonalities between them, the cave paintings exercise a palpable sense of universality which bridges us to the prehistoric humans. There have been a great lot of talented painters, yet many of these have not had the ability to properly paint expressions. Zorn, Géricault, and Sargent are some of the relatively few who could properly communicate a face onto the canvas. Such an ability is not necessarily dependent on a knack for the lifelike; the Fayum portraits possess a similar air while being less constrained to realism.

II

The universality presented to us by Chauvet and Lascaux is partly driven by the lack of context around them. The unknown is the greatest, and most available, source of mysticism that humans possess. The lack of knowledge surrounding prehistory imbues all that comes from it with this air. The greatest mystery of Chauvet and Lascaux is not one that comes from a lack of information, in fact, it is a mystery which only pertains to the paintings themselves. The great enigma of these works is that the people behind them – whoever they are – have proved themselves to be no different than we are. It is tempting to portray prehistoric humanity in a tongue-in-cheek fashion – humanity was no doubt lagging a bit behind prior to agricultural society. For our own benefit, we present ourselves as more capable, intelligent and more conscious than the cavemen were. This belief comes no doubt from humanity's impossibility of pinpointing the elusive origin of self-consciousness, which moved us from the animal to the human.

…the advent of art as aesthetic practice emerges as the dawn of a particular form of being-in-the-world: a humanity that is conscious of its own stepping-into-the-world as an exit from a previous world. In this newly created world, the world that is set up in and through the work of art, the human’s being-in-the-world ceases to be a self-evident given but rather becomes an abiding question mark. In the wake of the birth of the human through the advent of art, essential questions pertaining to what it means to be human, how to conceive of inhibiting a world in this or that way, and how to relate to finitude are cast into sharp relief as the guiding framework of experience.

– Gerhard Richter in This Great Allegory: On World-Decay and World-Opening in the Work of Art

To imagine the birth of humanity as being led by art is of course a very romantic idea, delighting anyone who has a particular inclination toward it. In fact, the sacredness of these works was perceived by Georges Bataille, who was granted permission to visit the Lascaux caves for a study of his intitulated Prehistoric Painting: Lascaux or the Birth of Art. He differs from most post-structuralists in his fascination for the origin. He bordered on being a mystic, holding a larger fascination than most of his contemporaries regarding the occult. Why do we feel that there is something occult about the prehistoric works of art?

Nothing in them suggests an outright mythicalness. In fact, their character is largely informed by the sentiment anyone has while observing them – that its creators were no different than we are. We can look at medieval paintings, or even later ones, and find inconsistencies they possess in regards to our realities – in animals, in children, or size – they remind us of the distance they have from us. What is even more remarkable is that these were considered great works of art for their age(!). These paintings have undeniable merit, but they aren’t always as lifelike as they would want to be.

On the other hand, the artist(s) of Chauvet and Lascaux, who were not raised to paint by masters, managed to portray their life with a perceptible ease. There wasn’t always anatomical correctness, yet that has been proven to be secondary. Even artists with complete knowledge of the ins and outs of a body have failed to piece them into a convincing human. What the cave paintings possess is something different than knowledge. Perhaps it was intuition, or nature, or something else.

Apparently art did not begin clumsily. The eyes and hands of the first painters and engravers were as fine as any that came later. There was a grace from the start. This is the mystery, isn’t it?

– John Berger in PORTRAITS: JOHN BERGER ON ARTISTS

III

We can hypothesise on the ‘meaning’ behind the cave paintings, whether they were ritualistic, or within the simple goal of mimesis. Hopefully we will never know. Similarly, I hope to never know the person behind them. It is such a great gift to be given these works possessing such grace and sensibility, and to know nothing of them. They acquire a paradoxical quality of being both alien and human.

It is always the case that interpretation of this type indicates a dissatisfaction (conscious or unconscious) with the work, a wish to replace it by something else. Interpretation, based on the highly dubious theory that a work of art is composed of items of content, violates art. It makes art into an article for use, for arrangement into a mental scheme of categories.

– Susan Sontag, in Against Interpretation

The people who lived tens of thousands of years before us were blessed with an ability which we will never be able to regain; they had the potential to be impenetrable. What we today find in religion, or in “great” scientific mysteries was their primary quality. If humanity today is still in terror when faced with this perplexity, we can only imagine what the prehistoric man faced, as he just emerged into consciousness. This freedom from endless narration and figuration was similarly showcased in mediaeval iconographical art. We were greatly mistaken to assume that the discovery of perspective was the great advancement for art.

When experts pretend that they can see here ‘the beginnings of perspective’, they are falling into a deep, anachronistic trap. Pictorial systems of perspective are architectural and urban – depending upon the window and the door. Nomadic ‘perspective’ is about coexistence, not about distance.

– John Berger in PORTRAITS: JOHN BERGER ON ARTISTS

This is what Christian painting had already discovered in the religious sentiment: a properly pictorial atheism, where one could adhere literally to the idea that God must not be represented. With God – but also with Christ, the Virgin, and even Hell – lines, colors, and movements are freed from the demands of representation. The Figures are lifted up, or doubled over, or contorted, freed from all figuration. They no longer have anything to represent or narrate, since in this domain they are content to refer to the existing code of the Church.

– Gilles Deleuze in Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation

Chauvet and Lascaux should not be figured out, and God forbid someone in the future who manages to do so. There have been a great amount of artworks that have stunned their observers; it is one of the continuous tasks that artists try to embark on. To find some piece of art that cannot be figured out is the greatest opportunity to be freed from this endlessly mimetic interpretation.

Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

– Walter Benjamin in Theses on the Philosophy of History

some favourites from recent museum visit

The Death of Öyvind Fahlström.

Anthropologists, Archeologues, and Historians would probably disagree, but this isn’t about them.